Selected recent presentations

-

‘See Britain First on Shell’: Modernism, Imperialism, and the British Petroleum Industry, Extractivism/Activism, The Paul Mellon Centre and Autograph, London, March 2023

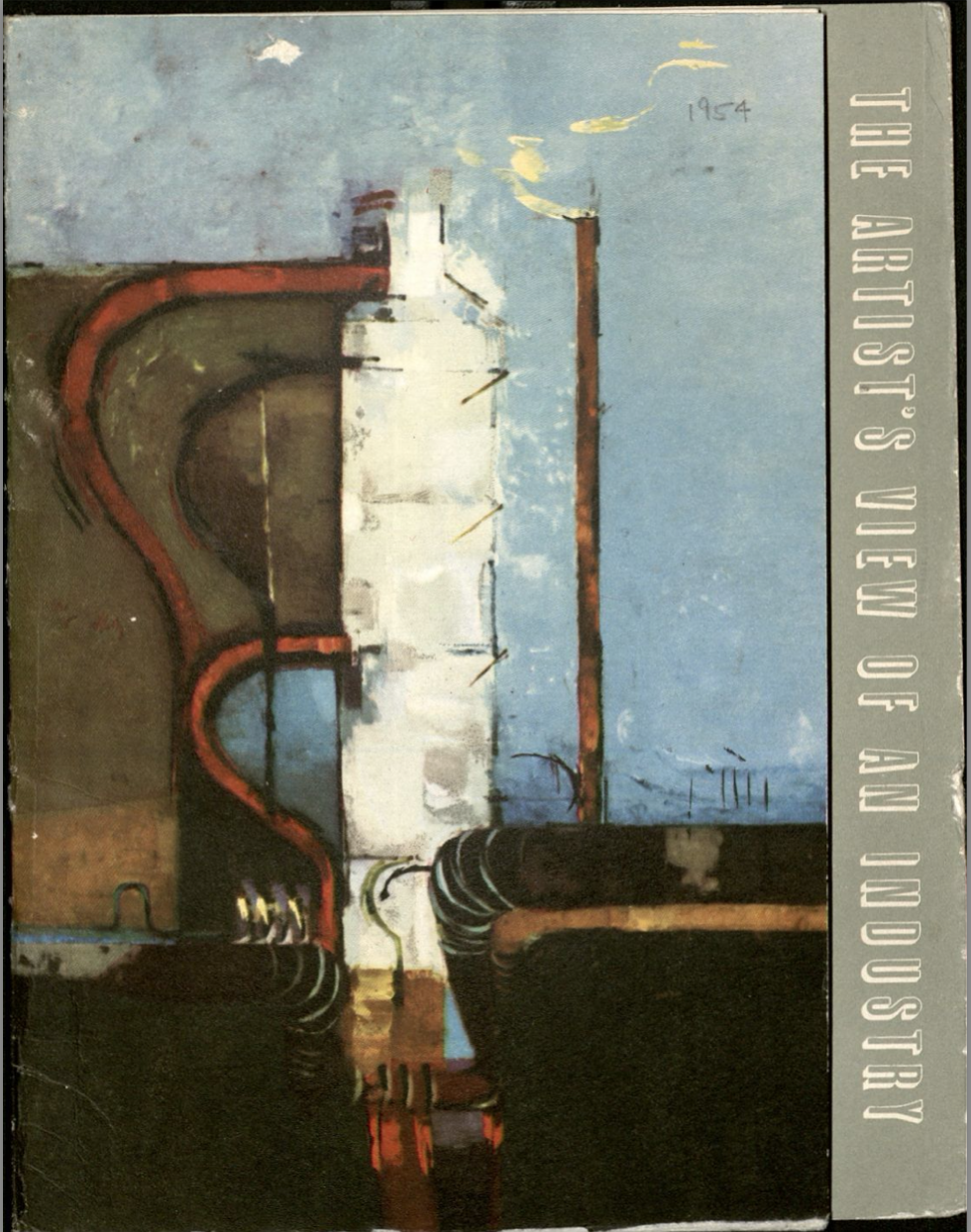

This paper demonstrates that Shell Oil’s twentieth-century art patronage was an early, and consequential, expression of the mutual influence of art and energy production. Acknowledging the contemporary work of groups like Liberate Tate and Just Stop Oil, I historicize petrocapitalist involvement with the arts as part of a longstanding project of corporate myth-making that used modernist art to enhance the power of oil regimes. I begin in the interwar period, when Shell commissioned advertisements from prominent British modernists that read “See Britain First on Shell” against bucolic backgrounds. I show that, instead, the extreme visual and physical violence of extractive industry was wrought on foreign soil. After World War II, however, Shell shifted its representational approach to normalize industrial infrastructure in the domestic sphere. In 1955, Shell commissioned young British artists to travel to UK refineries. The resulting images, shown in a travelling exhibition titled The Artist’s View of an Industry, depicted the infrastructure that contained petroleum: oil tankers, pipes, and storage tanks. This visual approach, though purportedly more focused on industrial development than the earlier advertisements, still obscured the human and environmental impact of global petroleum production.

-

Turner’s Pencil: Graphite Landscapes and Extractive Industry J.M.W Turner: State of the Field Symposium, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, September 2023

In 1797, J.M.W. Turner embarked on a sketching tour of England’s Lake District carrying a sketchbook and a graphite pencil. Amongst the drawings of dramatic mountain vistas, churches, and waterfalls from the 1797 trip, his notebooks contain two drawings of the landscape around the Borrowdale lead mine, the very site from which the graphite in his pencil was extracted. Cumbrian graphite mines were Europe’s principal source of graphite from the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries. These mines are the reason that the modern graphite pencil was invented. Graphite’s portability and capacity for varied mark making were essential to Turner’s sketching practice. Cumbrian graphite was synonymous with the pencil which, in turn, helped popularize the sketching tour, predicating Turner’s presence in the Lake District on the mineral composition of its topography. Though Turner’s sketches do not include a discernable trace of the mine’s industrial infrastructure, this paper reads between the drawings’ imprecise lines to reveal an encounter between artist and industrial landscape that was mediated through material.

-

‘Forms Emerging Out of Deep Darkness’: The Mine and British Abstraction Unseen Science and the Failure of the Visual, Association for Art History Annual Conference, April 2022

In mid-twentieth-century Britain, the strange subterranean darkness of the mine challenged representation. To imagine the human worker laboring inside this uncanny subversion of the visible landscape was to confront the uncomfortable origins of everyday substances like coal, oil, stone, and metal. Yet, this paper argues, artists were drawn to mining subjects precisely because they undermined artistic conventions. In the mine, perspective, line, and color dissolved, giving rise to unique pictorial possibilities. Faced with the obscure conditions of the mine, artists including Henry Moore and Bill Brandt turned to the texture and form of mined material as a novel method of engaging with the landscape. Exposing the industrial context of these materials proved that nature could participate in, instead of retreat from, mechanical innovation.

This work was an early precedent for postwar British abstraction, including the work of Prunella Clough and the St. Ives Group. While artists depicted other industrial spaces in this period, mines were unique in their affinity with abstraction. Though abstraction privileged natural form over the social context of the mine, a material focus maintained the markers of the fossil economy and the brutality of extraction on the picture plane. However, these images abstracted the body of the miner to a degree that severed the connection between the worker and the image. I argue that the collapse between miner and material in the visual arts was a symptom of the contradiction in the national attitude towards coal mining communities, whose labor products were vital to the national economy but whose living and working conditions remained largely invisible.

-

Minerals of the Island: Tracing the Fossil Landscapes of the 1951 Festival of Britain, British Art and Natural Forces, A State of the Field Research Programme, The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, London October 2020

This paper looks at two monumental artworks commissioned for the 1951 Festival of Britain: Origins of the Land by Graham Sutherland and Miners by Joseph Herman. Origins of the Land appeared in the “Land” pavilion, which traced the formation of Britain’s ancient fossil landscape, while Miners was used to illustrate the infrastructure of modern-day extraction in the “Minerals of the Island” pavilion. Yet, I argue, both paintings question the immutability of the human body in the realm of the industrial subterranean. The metallic figures that populate Sutherland’s Origins of the Land merge the body of the miner with the mechanical product of their labor. Herman’s miners, likewise, dissolve into the very material they are working to extract. The texture, color, and geometry of their bodies recall the earthly quality of mined material itself. Both compositions reveal the message of the Festival to be the merger of natural forces with the body of the worker.